by R V Branham

Injury, n. An offense next in degree of enormity to a slight.

— Ambrose Bierce, The Devil’s Dictionary

STAIRCASE: “What do you mean by this,” the urgent care admissions clerk asks.

— Pobrecito, todo chingado sin madrelike, todo Ground Control to Major Tomlike.

Geof Reid is at Sunnyside Medical Center, on an ambulance stretcher, waiting to be seen by a doctor, nurse practitioner, nurse, by a nurse’s aid, pillpusher, sawbones, homeopath, curandera, witch doctor, faith healer, psychic surgeon. (The ambulance and its attendants long gone.) At this point he’ll settle for a Psychic Friend. He probably needs, in fact, to start with Roentgenograms. Instead, he has an urgent care admissions clerk with claw-hammer eyes.

It is Geof’s fourth visit in two weeks — or is it his fifth? — They must be as sick of him as he is of them. He should ask Customer Services about renting a suite.

The first was when he brought in his son Drew for his annual check-up, annual shots.

Drew, barely eight, in eighth grade — taking Saturday seminars at PSU, Drew stuffed every science magazine he could find into his knapsack before they left.

The second visit was occasioned by Drew nearly having his right eye gouged out before or after earth science by a girl named Gretchen Triplette waiting for him on a staircase landing.

Drew nearly gouged Gretchen’s eye out, too. Good show, Drew’s grandpa would say, if still corporeal enough to be saying what grandpas say — and fortunately Gretchen’s father is a former associate of Geof’s father, so no attorneys were retained.

The third visit, he’d rather not think about. All the tubes leading into and out of his comatosely cyanotic father, yellowish uric or grenache white-wine-ishleachings or infusions.

This is his fourth visit.

No, it is his fifth visit, not his fourth.

The fourth visit, well let us draw a white hospital curtain around the amassed grieving and keening family members, an exploded view for a psychology textbook.

Geof came in a while ago by ambulance; since he has no actual identification with him, and even because the computers are down, they are sclerotic in attempts to verify account information. In the meantime he is strapped into a stretcher with a blanket the colour of a bruise or exit wound. Geof miserably tugs at his red goatee.

— His maternal abuela would have called him “Barbarosa.”

Even flat on a stretcher, Geof feels a tag team of sciatic agony sent up tingly legs to injured back and down to numb legs again.

Since he only remembers the first three of his Kaiser medical record numbers the urgent care admissions clerk asks questions so as to fill out forms. When asked his occupation he states “Film critic and crime beat reporter” and then adds “Landlord, really” and when the urgent care admissions clerk asks who he writes for he tells her, “Journal of the Plague Years: Northwest Music, Art, Sex, & Politics.” The urgent care admissions clerk says she doesn’t let her kids read that kind of trash, and then proceeds to tell him his name should have two ef’s at the end and he suggests she take it up with the hospital where his namesake and paternal grandfather was born. — At least she’s never seen his cable access show. If she had, the urgent care admissions clerk would no doubt have thoughts to share.

The computers must be back, because the urgent care admissions clerk is again in Geof’s face. “What do you mean by this,” the urgent care admissions clerk demands again.

He remembers her demanding before, she must have. “By what,” he says back.

“When I asked you, under ‘illness or injury.’ — ”

“And your question?”

“Under ‘illness or injury’ you said, ‘Staircase’…” From the first to the second floor of the apartment building is a gauntlet of children’s toys or parts thereof.

Plastic masts to sunken toy ships, tiny bazookas and bows-and-arrows of missing-in-action troops and exterminated tribes, hubcaps to thrashed toy cars, maimed animal toys from popular cartoon characters, all, from endangered species.

Geof’s eyes open.

He is fascinated by these toys jutting from coffee grounds and egg shells strewn down the staircase where he just now has stepped on a golden plastic mast to sail down the stairs.

No smooth sailing there. More a pell fucking mell leap into the void. More a tracking shot. Spine bumping against each step. Snakes. Ladders. With close-ups.

Dem bones. Eschatology recapitulating scatology, chakra by chakra. His brain hurts. Fractal zooms.

Eisenstein would never shoot this scene that way. Wenders, probably not. De Palma, maybe.

Pinned to the stairs by pain and disbelief, he reels in a recurring dream, a dream with a dream staircase guarded by a scrofulous dragon, a staircase he must climb in order to rescue his one-eyed son or his willfully blind father.

Father, son, distinctions here have no difference. It is a dream, after all.

They are in trouble, one or the other — son, father, grandfather — for getting into a fight at school and they do not want to discuss this with Geof, not even with a scrofulous dragon breathing brimstone down all their necks.

Geof has never felt that his father trusts or believes him, and detects skepticism from his son Drew. In this dream of stairs he has to reach them, explain. But the dragon… “Shit.”

Geof looks up to see the neighbor from the apartments across the courtyard. The neighbor who always tosses plastic bags of clotted sand and cat turds over the fence and back to the dumpster. — Thus causing Daphne to go yell at her whenever the burst plastic sends tapered cat turds and sand clots across adjoining carports.

The neighbor who has rowdy boyfriends over when her speedfreak plasterer husband’s gone, the neighbor whose slutty teeny-bop daughter Ginny stands outside the corner convenience store and asks strangers to buy PBR for her.

The neighbor whose two rugrat troll sons always leave these toys or trade up by trying to steal Drew’s GameBoy. — In exchange for which Drew is permitted by the older boy troll to pick on the younger.

The neighbor beaten by her speedfreak plasterer husband every other weekend. The speedfreak plasterer husband who has a Prince Charles-like chin — which is to say no chin at all at all; the speedfreak plasterer husband who never buckles up or makes the kids buckle up when tearing out of the alley at any and all hours in an Ebola-red truck with expired Idaho plates.

Geof, astonished, says to the neighbor:

“Was that an earthquake?”

“No.”

“Oh,” he says. Then:

“There’ve been a few rumbles, lately.”

“Yes,” the neighbor agrees, then, “not today.”

Then, “I heard the noise a while ago.”

“When?” he ponders.

The neighbor backs away. Her black eye has faded to smudges of amber and green just above the cheekbone. Like a Weegee classic New York City crime-pix retouched with hi-liter.

“I’ll call an ambulance.”

“I have Kaiser,” Geof is surprised to find himself say.

“Don’t move,” the neighbor with the Weegee eyes tells him.

“Don’t worry,” Geof reassures the neighbor.

As soon as she leaves he starts to get up, tries to, reaches for the stairs’ hand rails, pulls himself up, tries to, but the pain causes him to lose consciousness.

#

The dream dragon is more intent on guarding its hoarded treasure than in dealing with Geof, his son, or father.

Geof shouts for his son or father to go to their room, still time out, no videos, no Nintendo. He says they narrowly gouged that girl’s eye out. Yet when Geof raises his sword, the scrofulous dragon yawns and sparks of slag cascade down the staircase. Geof’s eyes close. “Left knee.”

“What?”

“Turn over, bend your left knee,” the Roentgenogram tech tells Geof.

“Left knee.”

He notices a tattoo on the Roentgenogram tech’s wrist, wants to ask if the tattoo motif is Celtic or Mayan. Or both.

What Geof says is, “It hurts.”

He hears a soft click of wooden beads.

“Don’t be such a wuss.”

Geof turns to see his wife Daphne. Braids newly beaded, nails, newly manicured, do not make her look any less harried, tired. Invoicing does that. But invoicing also provides medical bennies for both of them, including wrist braces she now wears.

Geof’s exwife works for State of Oregon Justice Department Child Support Unit and provides Drew’s medical bennies.

Daphne then tells Geof about his dad, about his mother phoning.

“Says it doesn’t look good. I think you should call her,” Daphne says, “No matter what kind of bastard your father’s been.”

“He never showed you respect…”

“Fuck that,” Daphne says, “Man tried hard. Behaved fine by me for a man who grew up in Kansas City in the 30s. What you mean is he never showed you respect, and that’s between you and him. Don’t pin that on me. Just call your mom.”

“They have our phone number.”

“Call your mom.” HOURGLASS:Geof Reid floats on a couple of ten milligram Flexoril tablets.

The TV is on, tuned to the Invertebrate Channel™, yet Geof hardly watches a black widow spider with secondary sexual characteristic belly markings, hardly watches a black widow spider devour her mate, in close-up, he barely registers her.

He recalls a thing his son Drew told him, about species of tiny spiders that eat the webs of black widows, steal their silk — and actually get away with it.

In fact, Geof does not so much watch video black widow predations directly, but watches, rather, the cathode reflected on a glass cabinet bearing familial bibelots and curiosities.

The only thing he acutely registers is his back. Geof hardly hears the laptop’s beep as its battery runs down.

He’s been following late-night Sunday drivebys online, seven dead so far this year, cutting and pasting for a research file — great article there, even a book. Lately, he hasn’t heard the driveby gunfire, the Flexoril knocking him out by then. His laptop is perched on a pile of biographies of Sergei Eisenstein, in English, Russian and in German — a PSU library overdue or two — biographies used as source material for his own bio on Eisenstein’s misadventures in Mejico with FridaKahlo and Leon Trotsky, a bio now languishing on an agent’s desk.

Somewhere in the pile are cassettes and cee-dees he is supposed to review. Most interesting one’s a vinyl ee-pee from a Mexican synthduo, Los Ambrose Bierces — and yes but does the world need Kurt Weill and Kraftwerk done in Spanish?

Geof hears the mail slot. Rent checks dropped through the slot he notices; those are set in a pigeonhole by the winecork-lined workstation.

Geof is never so fucked up as to ignore a succulent check fall into the mail slot. Never.

So fucked up.

A Reed alumni newsletter goes straight to the recycling bin, after peeling off unfranked Alice B. Toklas and Charles Bukowski stamps. — A postally-maimed New Yorker, Harper’s, and Drew’sScientific American and Science News are added to an ever-toppling pile of to-be-reads. — The black widow documentary sound is turned down. Speakers from the dining room and a carousel cee-dee player ensure hours of Keith Jarrett’s Sun Bear concerts. Almost Glenn Gould-like mewling and keening, pyropianisms.

Geof returns to the sofa, elevating and propping his legs against a sofa arm, his knees propped by pillows. He is distracted by wind blowing from the Columbia Gorge, blowing into Northeast Portland, leaves, shaking and rattling them loose to fly down to cover lawns and side-walks. Every time Geof, or Daphne, or Drew opens the front door, brittle amber-rust and purple-mottled leaves come rattling inside from up the stairwell.

Geof thinks about the voicemail messages. One is from a publicist, announcing a rescheduling of the director’s cut of something or other — the publicist accidentally hung up before revealing the movie’s title.

One is from his mother. He erased that. Another he erased before listening to.

Another, from Sam, his editor at Journal of the Plague Years, he wishes he’d saved. Sam wants revisions of his most recent piece. She does him the courtesy of discussing, negotiating, requested cuts or revisions. She detests complex sentences and makes him fight for every adjective, every semicolon.

And she always wants more theory, though expressed simply. Film theory. Political. Theological. Metaphysical. Linguistic. Anthropological. She loves systems, theories, philosophies — especially if accompanied by a cute anecdote. See Jane, See Jane signify — Geof hates theory to pieces.

At any rate, if he doesn’t get back to her within twentyfour hours, then she does what she deems best. Geof cannot recall when the bitch goddess left the message.

Should he call, negotiate?

Or was the erased message from the landscape guy?

Daphne told Geof to call the landscape guy, have him send a wetback out to rake up, sweep up, bag and haul away the leaves.

So Geof told her that the wind from the Gorge will only rattle more leaves loose just as soon as the landscape guy’s wetback rakes, sweeps, bags and hauls away the fallen ambermottled and purplerusted leaves.

Daphne said they’ll just call back the landscape guy and his wetback. And for all Geof knows, the landscape guy called and Geof fucked up, goofed, erased the message, consigned its digitized bytes to a telecomm hinterhell.

Geof notices the crimson hourglass of the black widow filter into his Flexoril fog. Notices red triangles drawn on the dee-vee-deejewelbox labels. There is a shitload of dee-vee-dees he has to return to a publicist — letterboxed foreign films mostly, scheduled for the film festival in late February. Amongst the dee-vee-dees is a rediscovered Chinese epic, a Sino-Soviet coproduction.

The only thing Geof likes about that particular film is the raggedy-clothed monk’s hourglass used to time the eternal warrior sent to confront a brimstone-breath dragon now residing in the verdigris-stained temple. Crimson of the black widow’s belly the same colour as the Chinese monk’s hourglass — the monk is actually the warrior’s father, and in penance for causing his mother’s death joined a Buddhist sect. Crimson the same colour as the sand in the three minute egg timer for calling time out when Geof or Daphne used to send Drew to his room for a few eternal minutes.

The worlds found in an egg timer. Turn the egg timer over and the sand runs back or forth twice, thrice, depending on the severity of Drew’s trespass, how many times he called them neofascists. Or shouted out that there were twelve gods during Mass, then rattling off Greek and Roman name variants before Daphne shut him up. But it has been years since they used the timer for that sort of thing.

A car horn outside honks.

Geof forgot to set the oven timer when he put the lasagna boxes into the oven. The horn again honks, his exwife’s horn. Geof and Daphne have Drew this weekend. He hears Drew bound up the stairs.

Then other steps, those of his ex-. What this time? He knows the child support check cleared; he always calls the bank to verify this. He hears Drew insert the key into the doorknob and turn it, then into the deadbolt, sees the door swing open.

“You’re letting the leaves blow in, Drew.”

Drew does not close the door. “Hi, dad,” he shouts, loaded with a knapsack and an overnight bag and hoisting a pile of thick books across the room. Geof sees a title: The Coming Plague. Drew comes to Geof, sets the books on the coffee table and the knapsack and overnight bag on to the floor before bending down to hug him. “Got any Pearl Jam,” his son asks, as usual. (Geof hates Pearl Jam, and Drew knows it.)

The eyepatch makes Drew look piratical. The visible (left) eye, hazel, is hard to read — blue is a recessive gene, hence Drew has inherited his mother’s almond hazel eyes.

Geof realizes he cannot smell his son; sinuses fucked up. Is it the bronchial asthma and æternalearnosethroat cycle of infections or the shot septum from the cocaine cowboy years?

His son Drew pulls away: “I smell some thing…are you burning the boxes again?” Drew makes for the kitchen.

“Careful with the oven,” Geof calls after him. “Grab the potholders.”

“Hey,” his ex- shouts to him from the stairs. “Better call nine-one-one. The slutty brat’s slutty brat next door is passed out on your lawn.”

“Again?” He slowly gets up. Tries to remember where he left the cordless phone.

The ex- comes through the doorway, wipes her feet, admits more leaves. He expects the ex- to ask him if he thinks she has put on any weight, to which he usually replies, “You’ve put on grams.” She doesn’t ask; and she hasn’t. The ex- wears a white crushed silk jacket with trashy goldcoloured silkscreen, “One-Cup-Wet-Noodle Dragon Lady” ensemble, she calls it — “One-Cup-Wet-Noodle” is a Japanese pejorative for premature ejaculators — referring to the time it would take a male college student to jerk into and hump a styrofoamnoodlecup. Geof turns to the ex-: “How do you know the slutty brat’s slutty brat’s a slutty brat?”

“Because Drew says she wanted to play Spin The Bottle with him.” Geof laughs; the ex- tries not to. “But. Really. ’S serious. Breathing’s irregular. She dies, her cunt mom sues your ass. Cunt mom sues, you and Daphne lose this place, file bankruptcy, move under the Morrison Bridge. And my son loses support checks.”

“That little slut: first name, Ginny.” Then: “You’d just be pissed about losing every other weekend to yourself.”

“You burned the lasagna again, dad,” Drew shouts from the kitchen.

“Again?” the ex- asks Geof.

From the kitchen: “Why are there leaves in the oven, dad?” Then: “I’ll make some bread.”

Drew makes bread from scratch; he learned from his maternal grandma and is extraordinarilly good at it and says he wants to have his own bakery when he grows up; has even enquired about getting an Employment Identification Number, like his grandma. Pounding and kneading dooes wonders for Drew, according to his school therapist.

“Be right back,” Geof calls to his son as he limps toward his ex-. “We have to go see a neighbor.”

“Just call nine-one-one,” his ex- says.

“Guy’s a drug dealer, I don’t want him to come over and blow us away.”

“A drug dealer? You have me dropping off my son —”

“Our son.”

“— to stay next door to a drug dealer.”

“Okay. Probably a drug dealer. Possibly. Maybe just a speed freak, probably too whitetrash for černobyl. Possibly. And there’s a drug dealer on every corner of every neighborhood in this town, so don’t bust my balls. Let’s just go get her mom, she was decent enough to call an ambulance when I fell.”

Going down the stairs after his ex-, Geof finds himself thinking of his ex-’s ghostly gash of a Cesarean section scar, a silver lining that Geof always finds — Oedipally? — adorably sexy — he was himself delivered by Cesarean section; the ex- is completely unselfconsiouslike about hers, wearing the skimpiest of twopiecers by cigarettestub-, and sodacan-, littered poolside or by she-scours-oilspilt-seashore.

Daphne too has a cute ghost of surgical incision scar, from a premetastatic ovarian surgery. Such a tiny scar for such a major event.

“You said her kids leaving toys on the staircase are what caused the accident.” Then, looking at him: “What’s with the wamble?”

“The what?”

“That staggering limp! You’re such a ham.”

“I have a back injury, you know.”

“A back injury, the drama queen says.”

“I get an MRI next week.”

“They only do it because you have the insurance.”

“I might need surgery, might need traction.”

“My mom was in traction for months and she didn’t bitch about it.”

“That’s what my other wife says.”

The slutty daughter of the slutty mother is passed out on the lawn, between the birdfeeder and the sundial, sweater and tshirt bunching up towards her shoulders, skin turning a goosepimply blue to match the pale winter sky. She is on her side, clutching a notebook with cutesy kitty decals on it, drooling on to blades of grass and broken bottleshard.

The name “GINNY” is written in a script not unlike graffiti gracing the neighborhood.

“Breathing’s okay,” Geof says and pulls the sweater and tshirt back down, “Who’s the drama queen? Look we can do three things here: Rape her, rape and kill her, or just get her mom over here.”

“What about just killing her? You forgot that option. Just like a male.”

“Let’s just go get her mom. Remember when you passed out in the swimming pool?” Geof is halfway across the courtyard when he is bashed by a flying video cassette tape.

“I tell you what I’m doing!” His ex- rushes to his apartment building, to his apartment. “I’m calling the cops!”

She rushes back upstairs.

Geof feels his forehead, runs his hand through his thinning hair, smearing a trail across his bleeding scalp.

The videotape is a Multnomah County Library VHS in a clear plastic case. The Wizard Of Oz.

There was an hourglass in that film, wasn’t there?

The neighbor and her plasterer husband slam each other across the livingroom of their apartment like anorexic sumo wrestlers.

The torn garnet curtain and picture window lends their fight a theatrical flair.

Sirens call from the distance.

The neighbors stop fighting.

The plasterer husband hooks the curtains back up, ignoring Geof’s hand-waving. The neighbors crank up the radio to Classic Rock. Aerosmith.

Geof turns around.

Dream On.

The police are still with the neighbors when Geof’s ex- leaves him with their son. An ambulance has already taken the slutty brat away from the front lawn.

A police tank arrives, parks across the street.

“Don’t let Drew see any of those Hong Kong movies,” the ex- tells Geof as she hugs Drew goodbye. Then, to Geof:

“Too fucking violent… Shoving chopsticks up someone’s nose to kill them. That’s sick.”

“That’s a Japanese Yakuza movie.”

“Then no Yakuza movies, either. And call your mom.”

“Daphne put you up to this?”

“Yes. Who gives a rat’s assignation about your father? Who cares if he never believed you?”

“I care.”

“Christ. If I hear one more time about how your dad didn’t back you up when you were caught plagiarizing that thesis —”

“He didn’t, and I didn’t.”

“That thesis you’d written for someone else, right?”

“My exact point.”

“You’d been paid top dollar for that thesis, that thesis that you’d submitted a year before. It was dishonest of you to ‘recycle’ it. And lazy.”

“It wasn’t theft.”

“Yes. It was.”

“Wasn’t plagiarism — can’t be theft from myself. There was no explicit contract forbidding reuse.”

“There was an implicit contract,” she says, finding herself sucked in.

“Was not.”

“Who cares — You weren’t expelled, or even failed. Unlike the lazy ass who paid you for that thesis. And no jury in heaven, purgatory, or hell would have convicted that lazy ass if he had wasted your sorry sadsack ass after being expelled, all you had to do was write another one —”

“— Just write another one, are you insane — ?”

“— Your mom backed you up during all of that self-inflicted horse shit, you’ve told me. Your mom’s a saint, so call her. Don’t be an asshole.” She smiles sarcastic. “You are a lucky seventh idiot bastard son of an idiot bastard son.”

“How is that?”

“I like Daphne. She’s good people. You marry a good person who then inherits an apartment building. Lucky.”

“We still pay a mortgage.”

The ex- waves her hand.

“My rent’s twice your mortgage, and you’ve got six units!”

Then, pointing at the apartments across the courtyard, the ex- adds:

“Call my pager if any thing happens. And if any thing happens to Drew, you will die.”

“Show’s over. Cops’re here. Nothing’ll happen.”

The ex- gives a final dismissive wave:

“Exit stage left.”

The knock-down dragout fight across the courtyard starts up again when the police and their police tank and black marias with their “The City That Works It” painted on their doors finally depart. SUNDIAL: There is a sere sundial on the lawn in front of Geof’s and Daphne’s apartment building — it is a northern exposure and gets no light ever.

And spiky moss covers the north side of the pedestal, all micro triffidlike.

The day is clear but cold; clouds approach, perhaps bearing more rain.

Geof wears one of his favorite winter coats, sheared from alpacas, from the altiplanos of South America.

His father, he remembers, gave this to him when he graduated from college. They weren’t speaking at that point, but did still exchange gifts at the appropriate holidays or milestone occasions.

There is broken glass from bottles of rotgut wine and malt liquor at the base of the sundial, along with tapered pale garlands of album græcum.

Drew could cut himself on that glass. — And the ex- would never let him forget, if she let him live.

And hair there, hair the colour of microbrew pale ale everywhere on the lawn, as if some body got her or his hair cut by a marine corps barber.

One of the rugrat trolls from across the courtyard has hair that colour — the one Drew picks on. Geof remembers some thing from his childhood, a specific act of logical cruelty involving someone’s hair. He cannot recall the colour but the memory creeps him out.

The hair and the glass also makes him think of his so very-recently-dead father appearing to him in a dream the night before, saying he wasn’t dead, was really in the Witness Protection Program and might not be able to drop around for a while, and of course it being a dream there was a test and his father was administering the test and accusing him of cheating before the test even began, saying Geof lacked Ethics and railing against Kids Today! — His father who made a smallish large fortune in a rotten real estate venture and then spent half that money hiring attorneys to finesse the legal fallout.

Geof sees the Nation of Islam neighbor from across the street walk past with a bag of groceries. He greets him and waves and the Nation of Islam neighbor flips him off. A middle fukka-you-ofay-redneck-cracker finger.

Whenever he tells Daphne or the ex- that he wishes there were more Nation of Islam members in the neighborhood, they tell him he is so full of shit an enema could not save him.

At this point he tells them of seeing the Nation of Islam neighbor chase away dealers, backed up by his shotgun-toting wife.

At this point Daphne asks why they still have cracker white trash tweaker neighbors.

Geof frowns as he cuts across the lawn, past the sundial, to get into his car, a Hyundai. He’s been so wanting to clean the broken glass up since he noticed it last week but he has too many appointments today. “Just lie down,” the MRI technician tells Geof.

Geof, dressed in a paper gown, feels a cold draft on his testicles and dick. “Can I ask you some thing,” he asks the technician.

“Okay.”

“Do I smell bad?”

“What?”

“Do I smell funny?” Then, “Never mind. Forget it.”

The technician looks at him.

“…This’ll take about forty-five minutes altogether. Some people find this very uncomfortable, but it’s not painful.”

Geof lies down on what could be an examining table at the foot of what could be a very large frontloading laundromat dryer, the one into which half the planet’s left socks vanish.

“And don’t move,” the technician tells him and then leaves the room.

The table moves, the table Geof is lying on, taking him from the gleaming white room with its toobright lights, and he is inserted into the chamber. He remembers a scene from a Kubrick.

“Open the pod doors, HAL,” Geof says.

“…’Smatter,” the technician says. “You okay?”

“Fine,” Geof says.

“What,” the technician says.

Looking up, he sees light reflected from the room outside into the chrome rim of the chamber.

There is a series of percussive movements in the Magnetic Resonance Imaging Chamber as the MRI reverses the magnetic spin of Geof’s very atoms, allowing sagittal, double-echo sagittal, and axial images to be taken through his lumbar spine.

He knows these anatomic terms because he glanced at the technician’s notes — “lumbar” seems redundant. The percussive noises remind Geof of the Bang On A Can Festival he went to in New York years ago. A white of Christmas light bulbs dances in the trees as Geof heads downtown, cutting through the redbrick warehouse labyrinth of the eastside industrial district.

The palimpsest of cobblestone, abandoned rail track, and worn asphalt is hell on the tires.

He makes the Hawthorne bridge, westbound. But the bridge has been raised so a boat can pass, so he has to stop — this steelgrated bridge gets icy in the season of misted burgeoning skylines but really is the best route to downtown. Geof turns on the radio for news about the recent drivebys but there is only more Truth & Forgiveness Hearings crap — so what’s with the “The Secret War”? Nothing secret about shoot outs at federal buildings all over the country — couldn’t get a passport without being caught in some god damn faction’s crosshairs, so why not just call it by its real name, “The Dirty Little”?

He tunes in-to NRK, to a song sung by The Presidents Of The United States of America, about stepping on kittycats.

Geof looks up, a mere glance, at the soon-to-be federal court building, at the arcs of welders, splatter and slag sparking down with the drizzle, splashing against the girders. He thinks of the dream dragon.

Thinks of his father, who never believed him when he said he hadn’t taken the change from his father’s coin roll to buy comic books. — Fantastic Four and Spiderman, his favorites from Marvel, and The Flash and Green Lantern, from DC. — He thinks of the workers up on the girders — must be nativeamerican — after all, Mohawks built the Empire State and Chrysler Buildings, half the bridges in Canada and New England. — Thinks of the Ojibwa Chippewa on his father’s side of the family, of the Huichol, Pima, Comanche, Sinaloa, and Maya on his mother’s. — Splatter and slag. Red lights ahead. — His father never apologized after later finding the coin roll in his car. Striped wood and aluminum arms lower to block traffic as the bridge is raised to let a boat pass.

Geof slows, gently taps the brake, and skids into the jeep in front of him. He gets out and the burly driver of the jeep in front of him gets out. “Wwwawatch it, jjjjejerkoff.”

The stammering jeep driver has lime-green hair.

Geof starts to apologize and the other driver continues to berate him. There is no apparent damage to either car. “Look,” Geof declares. “Nothing happened.”

“You wwuwere lucky, ffffufuckwad.”

“We were both lucky.” Geof checks on his father before picking up his son from the optometrist appointment. — Daphne volunteered for overtime today, and already dropped Drew off at the doctor’s.

He sees John Triplette, an associate from his father’s public relations firm, and nods slightly to him. His mom Dora is in the back row, away from the stink of floral arrays, with friends and relatives Geof barely remembers or recognizes — except for slacker dyke sister Gloria and her cocksure turkeybaster kid with two effs in his name. It has been years since Geof saw his nephew and he is amazed how the vicious little bastard’s grown.

And truth be told, Geof has no quarrel with dykes, turkeybasters, or vicious little bastard nephews, once indeed having shot his spunky wad into the pool so to speak for a trustafaridykester who dropped out of college in her third trimester and — last he’s heard — teaches at Rutgers University.

The ex- is there, too, wearing her “Fuck-Me-On-The-Stairs” jacket, and slung on her shoulder is a pink fur-lined valise like a cunt.

“Daphne had to do overtime.” He manages to choke back sobs as his mother hugs him.

“¿Porqué no visitas?”

“Pardona me. Yofue. Miinfermidad. Pardona me.” Geof goes to the front. Checks his father.

Yup, still dead. Favorite watch, an old Rolex. Favorite shirt and tie, a bit faggy. But his father was a dandy and liked to shock his pallsywallsies on the green. Favorite ring, Princeton, Class of 1946.

The cosmetologist made his father look to be wholly foolish, a defanged and deballed lion, a sacred clown. These rituals, he thinks, are too ironic to be barbaric.

“I just.” He finds napkins in his altiplano jacket, paper napkins from Coffee People, some already stained with coffee and crystallized snot, and uses the cleaner ones to wipe greasepaint away from his father’s collapsed face.

An event horizon to the black hole of death.

“Just wanted to.” He wants to say some thing sarcastic and spiteful and unforgivable — a cut or fade to black, not a dissolve, wants to tell the old man he just wanted to make sure it was him and wants every body to hear him say this but the words fail to ignite and the flames catch in his throat, sparks descend down the stairwell, slag and splatter, back down his gullet.

#

Geof picks up his son from the doctor’s before going to the screening. He can tell Drew knows he’s been crying — though he doesn’t know what or if the ex- told his son about grandpa — and can count on Drew to say nothing to him about it. Drew asks how there can be measurable objects in the universe, like quasars, that are apparently five billion years older than the known universe.

“Because they are remnants of the universe before?”

“Exactly!” Drew laughs. “Exactly!” Then: “And the math on this is a real bitch.”

“Watch your fucking mouth.”

Drew laughs.

“No. Seriously. And don’t tell your mom I took you to this film.”

“Why?”

“She’ll bust my chops.”

“…Why doesn’t mom like action movies?”

“She thinks cinematic violence is bad for kids.”

“Our teacher says that about cable TV programming.”

He considers telling Drew she’s probably right, but for the wrong reason: Cable’s just subfuckin’moronic.

Instead he says, “Just look at me, Drew. I’ve seen twenty thousand films; half containing an average of, say, twenty-point-five killings. — I’ve seen —”

“Four-hundred-and-ten-thousand,” his son tallies.

“Yeah. I’ve seen four-hundred-and-ten-thousand people killed. So just look at me.”

His son laughs: “You’re a weirdo, dad.”

The Movie Palace is in a splendid old brick building, unassuming and plain on the outside, elegant on the inside.

A former British Consulate, then Freemason temple, it still has its original chandeliers, ornately carved ceiling, mezzanine with crimson carpet and leather chairs set in front of backgammon tables or chessboards, the odd presidents’ deathmaskmothattacked Oriental rug, and a courtyard with ferns, fountain, and verdigrismottled sundial.

Geof is lucky enough to find a parking space.

His watch indicates he is half an hour late — which should make him fifteen minutes early.

These things run on Standard Publicist Time. The marquee reads:

ONE COP, ONE CROOK, 10,000 BULLETS …

“Look at that.” Drew points to a car parked in front of them, a Silver Cloud Rolls Royce. — Geof shrugs: “So?” — Drew points at the Silver Cloud’s bumper sticker: “LIVE SIMPLY SO THAT OTHERS MAY SIMPLY LIVE.” — “That,” Geof says, managing not to laugh, “has a certain elegant entitlement.” — Drew sees a bento cart at the next corner. — “Can we get teriyaki?” — “After the movie.”

Geof and his son pass through metal detectors, which go off.

A tattooed woman wrestling with the popcorn machine basket waves them through.

“Sorry, I forgot to turn off the damn things.”

Inside the theatre, the usual crew:

Sergei, the mad Russian Stumptown Senator & Sun third-stringer, with the odd byline in Fangoria or Spin — also Veep of the PSU Film Society — and so soon departing for Mexico and Guatemala on his annual workstudyhejira — credits to go towards his interdisciplinary archæology and film production degrees.

Marvelous Harve, the Portlandic Weekly Herald & Argus film critic and presskit whore with knapsack and taped-together hornrim glasses.

Cecilia, a fellow Reedie who writes for a biweekly Eugene anarcho-slacker staplezine called The Snark, as well as for Stumptown Sputnik (which doesn’t take any adult advertising because they have integrity, and doesn’t pay anyone, especially when they promise to do so).

She is excited about a piece she just sold to Twist, after getting a killfee from Sulky.

Every body says hi to Drew, compliments him on his eyepatch. Every body compares various blue, yellow, and white asthma guns with the child’s — commenting on which look all scifi movie space ship miniaturelike, then asks him when he’s going to write his first review.

“Do I smell funny,” Geof asks Cecilia and Sergei.

They laugh; look at him, each saying, “No.”

“My doctor says I smell funny. I shower.”

“He does,” Drew affirms.

With or without Drew, Geof always sits with Sergei and Cecilia, who always whisper to each other throughout the film. Usually, the film at hand is so awful Drew does not much mind. Sometimes Drew asks them to please shut up.

Marvelous Harve always sits a few rows to the front of every body, making a point of having a notepad and tiny flash-light. Two minutes after the opening credits Harve gets up. — Two minutes after the opening credits Harve always gets up.

Cecilia whispers to Sergei, “What do you think?”

“I bet five he does.”

“I bet a cappuccino that he does.”

“Hey,” Cecilia whispers to Sergei, pointing at a gentleman with a very small bald spot and a very long ponytail who sits several rows in front of them. “Isn’t that Stella Capra’s husband, Uggo?”

“Ssshhhhhh.”

“Think he knows you porked his wife last year?”

“Uggo?” Sergei asks, “where?” Then, seeing him: “Oh, yeah. You know, he heads Television Studies now.”

“Ssshhhhhh.”

“Hey Uggo,” Geof starts to call out but Sergei kicks him hard as the lights dim, the curtains open. Show time.

On screen the Hong Kong cop hero tells of his immigrant petty criminal Yakuza father who repeatedly accused him of stealing when he was a small child, who never believed him when he denied it and accused him of lying and beat him with kendo shinai; and how there was trouble and his mother died and the neighborhood went kaboom (or boom, ka-) (there are issues of dialect as well as dialectic, to say nothing of how to express the postindustrial quasispectral world in still-Taoist ideograms) and his father disappeared into the endless Hong Kong Triad backalley underworld, fading to black, and he was raised by his uncle and aunt and grandmother.

The Hong Kong cop relates this to a colleague while shoplifting bootlegged merchandise in a department store.

In a repeated scene, not quite a leitmotif, the Hong Kong cop hero keeps going back to what is left of his old neighborhood — shoplifting in markets and boutiques, most rebuilt since the boom, ka-.

The cop hero stands in front of a metastasized glowing tin shed of a factory with pincers extruding from the roof all Japanese atomic crabmonsterlike and backflashes to his smiling mother singing him to sleep and then the neighborhood going boom, ka-, everything flying, seeking its own vector as order unfolds into resplendent chaos.

#

Marvelous Harve eventually comes back into the theatre with popcorn and a candy bar. Gets up a few minutes later.

After the film villain named Dragon, who runs a Hong Kong Triad, is shot, stabbed, immolated, and defenestrated from the balcony of a luxe suite on to a staircase floors below, to then crash through the landing rail and be impaled on a sundial in the garden below that — all this done to the Dragon by his long-lost son who has become the shoplifting policeman; after the Chinese credits with French subtitles roll by. Drew reminds his father Geof of the bento cart. Geof gives him a ten dollar bill. “Get me chicken with rice and just a splash of teriyaki.”

“The noodles are better.”

“I want rice.”

After the publicist gives every body press kits and posters and tshirts and key chains and cee-dee soundtracks, every body goes back down to the lobby to get the newest Portlandic Weekly Herald & Argus.

Marvelous Harve dismissively waves to them as he exits the building, clutching a Portlandic Weekly Herald & Argus. Drew returns with a white plastic bag containing black bento trays.

Geof has already grabbed the new Portlandic Weekly Herald & Argus from a lopsiding lobby news rack, and is checking it against last week’s press releases.

“Sergei. You owe me a cappuccino for last week.”

“Hey!” A hand grabs Sergei’s shoulder. “Good to see you guy.” Uggo’s hand. Sergei jumps out of, then back into, his skin.

“Oh — oh — Uggo!”

“You still owe me a term paper, guy.” Uggo looks at his watch. “Have to pick up the noneck monstrosity from day care.” Then to Geof: “What happened to your cable show?”

“It was just a temporary gig,” Geof says.

But Uggo is out the door. As he departs, Cecilia turns to Sergei: “He knows.”

“Nah,” Sergei says. “He doesn’t. He can’t.”

“I heard he likes to watch,” Cecilia says.

“Besides, who cares what a trophy-hyphenator thinks.”

“A trophy-what?”

“He was married once before, and he has not one, but two hyphenates for his last name.”

The publicist arrives with a tray of cappuccinos. “Gotta make like a particle and split,” she says and does so. Every body goes out to the courtyard, with its gurgling fountain and black and white floor tiles looking like a barbershop where Mafioso get whacked or like an infinite chess board where the Red Queen demands decapitations, and where a few white tables and plastic chairs are set up. They find a table that isn’t too wobbly or filthy and find chairs that aren’t cracked or chipped or covered with bird shit and drag them to their table and then they sit.

Drew takes each ribbed ebony sarcophagus from the bag and passes the one with the rice to his dad. “Anyone else want any,” he asks the group as he passes a pair of chopsticks to his dad. “I can go get some more.” Sergei and Cecelia decline. “I didn’t know she was in on the bet,” Drew says.

“You kidding,” Sergei replies. “She started the tradition.”

“At least Marvelous Harve didn’t stay to lecture us about how film’s gone dead up the ass ever since Fassbinder died —”

“I’ve seen a few,” Drew says, “a bit Angsty but they’re not bad.”

“Listen to the kid tell us about Angst,” Sergei says. “The only thing you need to know about Fassbinder is that he made fifty movies in twelve years, some of them over eight hours long, and most perfectly calibrated in one way or another but only in one way or another — and he died at his editing table of a heroin-cocaine overdose and that you need to do lots of coke or heroin to get into his films. But. You’re a kid and we don’t talk about that around kids. Marvelous Harve always rewinds to a particular scene in Fassbinder’sLola — I think it was Lola — he’ll go on and on about Fassbinder setting up an impossible scene where his male and female leads are in a parklot at night and are about to kiss and the audience wonders how they’ll pull off the shot off because the actor is lit with blue gels and the actress with soft red gels and just then as the two’re about to kiss they turn and hold up their arms because of the whitelightwhiteheat glare of a large automobile’s headlights as it comes into the lot.”

“And since he’s not here you’ve got to repeat it verbatim,” Cecilia comments.

“Look.” Sergei turns to her. “I’m warning him, okay?

“Speaking of warning. Got all your boostershots?” Geof enquires.

“Of course.”

“So.” Cecilia continues: “Going to bone your teacher Stella again this year?”

“The kid,” Sergei mutters, pointing to Drew.

“Stella Capra?” Drew asks.

“Yeah,” Cecilia says.

“I audited her Mayan astronomy course last summer.”

“Go on,” Sergei says to Cecilia, “Go on. Ask Drew if he boned her —”

Drew blushes as Cecilia and Geof do doubletakes. Cecilia starts in: “You should watch what you say around kids —”

“It’s okay,” Drew says to her. Then to Sergei: “I’m not that precocious —”

“I should hope not,” says Cecilia.

“Besides,” Drew adds, “her grasp of geology is shaky at best, and she’s over-rated as a Mayanologist.”

Geof picks at his sarcophagus of bowl and stops when a crimson drop falls onto his white rice.

“You okay?” Cecelia asks him. Another drop falls, then another, another.

“That’s disgusting,” Sergei says.

“Shut up, Sergei,” Cecelia says. Then to Drew: “Go to the restroom, and get a bunch of paper towels. Dampen them.” And then to Geof, “Tilt your head back.”

“I’m okay. I get these sometimes.”

“Tilt your head back.”

“Yes, mother.”

“Just shut the fuck up, Geof, and tilt your head back. And call your doctor’s advice nurse when you get home.” The bleeding stops, gradually. They drink another round of cappuccinos in the courtyard, watch the brief afternoon sun do its shadows and light dance with the sundial — and try to ignore the dandruff kernels and popcorn flakes on Sergei’s black tshirt — and discuss the office politics of their various publications, and all the vaccines needed whenever going abroad.

Cecilia astonishes every body by telling of attempts to impregnate herself with the services of a local fertility clinic. Actually, she explains, they have fertilized Andrea’s eggs and implanted one in Cecilia, or tried to. That way they are both the parents.

She also tells of an incident a few months back where they initially decided to go lo-tech turkey baster and they had three guys doing a circle jerk in a guest bedroom and when the cup was quarterfilled one of them took it into the dining room where Andrea would route it to their bedroom where Cecelia awaited the demon seed. Only there was a cable guy doing repair and after he used the bathroom he asked for coffee and thought that the cup had nondairy creamer, and afterwards wanted to know the brand. And the three guys were too tired and discouraged to try again. Hence, the fertility clinic route. And in a few years they want to implant a fertilized egg from Cecilia so that Andrea carries a baby to term, though not now. Right now, it’s Cecilia’s turn. “It’s just not working,” she finally says.

“But why,” Sergei asks, bemused, “why a baby?”

“My clock is ticking.”

“How does Andrea feel about it?”

“Andrea comes from a big family — she’s supportive.”

“Supportive?” Sergei laughs. “Supportive, good. I s’pose if she’s letting them suck out eggs and freeze them before popping them into you, I s’pose she’s supportive. You know you’re only twenty-five.”

Cecilia laughs.

“But my eggs aren’t going with the plan.”

“Silent sperm,” Drew says. Every body looks at him.

“There’s an article about environmental pollution and resultant reduced sperm motility. Pollution’s not the only factor.”

“Listen to him,” Sergei says.

Cecilia pauses, turns to Geof:

“Really sorry about your dad.”

“What about his father,” Sergei enquires. Then: “Geof never talks about his father.”

Geof reaches for his coffee and is tempted to ask her to pass the nondairy creamer. Cecilia looks at Geof. “Nothing,” she says to Sergei.

“He died,” Drew says, surprising Geof.

“You heard Cecilia,” Geof says to Sergei.

He looks at what was his lunch, looks at the black sarcophagus of bowl, at the white grains swamped by clotted blood. SAND: Geof and Drew go home.

This time Geof takes the Burnside Bridge across the sluggish-unto-sclerotic Willamette, to avoid any ice.

There are orangeorange cones funneling the traffic down to onelane each way and the flow slows as Geof and Drew merge into a queue. — The day has become overcast and a sullen bluegray glare is sent bouncing everywhere. — To the north Geof and Drew see the Steele and Broadway bridges and the immense Fremont Bridge of suicides, and to the south a glinting blur of metal rushing across the Morrison and (mostly hidden Hawthorne) bridge(s), and the doubledecked glittering bumpertobumper double-arch of the Marquam Bridge — the Marquam arcing as it takes I-5 across the Willamette, and shows off pretty city lights for outoftowners. Drew points out a billboard for the Gay Golf Channel™.

Drew next points out the river’s ripples below the Morrison Bridge, river water against bridge foundation piers and bridge against river water — slicing water into rippling vee-formations, and then reminds his father that none of the bridges are earthquakeproofed, and Geof says he’d rather not hear this right here right now.

Before the signal completely craps out they hear an old Ramones song on NRK, I Wanna Be Sedated, and Drew sings along. Drew comments to his dad above the bompbompabompa of the radio about how the car’s radials make strange and soothing musics in response to the buckling city streets around Lloyd Center. They take the freeway and Drew plays a favorite car game, calling out “Ouboros,” to which Geof replies, “Subaru?” There is a familiar homeless person at the Lloyd Center turn-off, with a sign: WILL WORK FOR FOOD.

“Why don’t you ever give him money, dad?”

“He’d spend it on —” Geof stops himself short; that is what his father would have said, that the bum would spend it on wine.

“You buy wine,” Drew says. “You probably have a case in the trunk. Give him a bottle.”

Geof pulls over, gets out and opens the Hyundai’s trunk; he runs back to the offramp panhandler and gives him a bottle of Italian merlot. The offramp panhandler tries to tell Geof he is in a 12-Step Program but Geof is running back to his car. The neighbors across the courtyard are at it again.

Drew is in the kitchen making foccacia when there is a loud pounding on the door: “Get that, dad.”

The knocking continues. Rugrat troll eyes glance at Geof through the mail slot as he goes to answer the door. The slot shuts.

“Hello,” the neighbor says to him, loudly. Geof can tell she is furious, by her agitated eyes, by the vein pulsing fiercely on her forehead, by the spittle flying with each word, and by the way she clutches at her little son, whose hair has been very badly shorn. “I know you laugh at us!” Her son looks like the kids you see in a cancer movie, when they do the obligatory children’s hospital scene. “I know,” the neighbor tells him, “I know you think we are white trash rednecks, but I want to know what sort of parents raise their boy up to do this to my baby!”

“What?” The hair on the lawn. “Drew,” Geof calls, no, yells, to his son. “Drew, right here, right now!”

“I don’t want to hear your son’s lying ass.”

She pivots to stomp back down the staircase, her whimpering redneck rugrat troll in tow.

Drew comes to his father, wiping his hands with a towel.

“I didn’t, dad. Honest.”

“Didn’t what…?” Geof regards his son, the lying son of a bitch.

“Whatever you’re going to blame me for, I didn’t.”

Downstairs in the courtyard there is screaming. Daphne is home, screaming at the neighbor: “You get your Jethro-clone redneck ass out there and clean up that sand and cat shit before I call the cops.”

“Kiss my white ass,” the neighbor calls back: “Look at what your boy did to my baby.”

“I don’t care if Drew cut his dick off and fed it to your cats,” Daphne is heard to reply. “Unless you clean up that sand and cat shit right now I’ll call your landlord.” There is scuffling and the sound of wood hitting flesh. The neighbor screams and uses the N-word and Daphne tells the neighbor to cunt off and the neighbor’s flipflops echo back across the courtyard. (Geof is a bit shocked at Daphne’s language, language Daphne picks up from her reading group, language Daphne picks up from the ex-.) Daphne storms up the steps.

“Honest. I didn’t, dad,” Drew repeats. A smile (incriminating?) forms on his face.

“Then who did,” Geof asks. He knows that smile ironic. From a slightly opened window, the voices of the neighbor and her speedfreak plasterer husband can be heard to converge: “Out.” — “Your.” — “My.” — “Out.” — “My.” — “Fucking whore.” — “Fucked Ginny.” —

“That’s it!” Daphne barges through with a janitor’s broom, slamming the door behind her. “That’s it, Geof! I’m calling their landlord!” She shuts the window. “I do not fucking need to hear that vile horse shit! Where’s the phone number?”

“On the fridge.”

Geof looks at his son.

“I didn’t do it, dad.”

“Where is the god damn telephone? Never mind, I found it.” Then, “I got there just in time, Geof. They were going to shut the lid to —” Daphne looks at Drew. “I talked to your mom, Geof.” She looks at her husband, turns away, and looks back. “You okay?”

“Fine.”

“You look like you should lie down.”

“Dad had another nosebleed today.”

Daphne turns to her stepson: “What do you mean another?”

The neighbors are still to be heard screaming in their downstairs apartment across the courtyard, voices now muffled, words unclear.

“Dad. I did not.”

“What,” Daphne says. To Geof: “What did he do?”

“Neighbor says Drew hurt her kid.”

“Did not.”

“Good. Brat deserved it, probably.”

Geof hates that, hates it when Daphne undercuts his authority. Geof sees his son Drew bite his tongue, trying not to smile or grin or show any expression, which terrifies Geof. Geof knows this one, too; has done it himself. He could slap that shitty smile off Drew’s face. “Like you didn’t try to poke the girl’s eye out?”

“Foccacia smells great,” Daphne says from the kitchen as she dials: “Hello.” Pauses, listens: “Voicemail sucks.” Then:

“Hello, this is Daphne Reid, owner of the apartments across the courtyard from yours. About your tenants in Apartment B.”

“I did not.” There are sirens, only they sound like they are going away, dopplering red shift. Gunshot. A bullet flies into the room, shatters the window, flying seconds per second, shatter and slug whizzing past Geof and Drew. Geof reaches for Drew, embraces his son, and they fall to the floor, fall to safety. There is then another gunshot. Again. From across the courtyard. Then another. Again. Daphne crawls to them. “I didn’t.”

Another. Not semi-. Still, the gunshots, the bullets, come. Again, again. Another. Another.

* * * * * * * * * * * * *

R.V. Branham was born & raised on the California/Baja border, & as an adolescent wound up in El-lay. When not co-hosting a floating æther-den, R.V. attended U.S.C., El Camino College, Cal State Dominguez Hills, & Michigan State University. Day jobs have included: technical typist, photo-researcher, x-ray tech. intern, interpreter, social worker, & Treasury Dept. terrorist. His short fiction has been published in magazines such as 2 Gyrls Quarterly, Back Brain Recluse (UK), Téma (Croatia), Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine, Midnight Graffiti, & Red Lemonade (online), & have been collected in such anthologies as Red Lemonade’s Hybrid beasts (available as an e-book), Full Spectrum 3, Drawn to Words, Mother Sun, & several Gardner Dozois anthologies; many of his short stories have been translated into Croatian, German, Japanese, & Spanish; his plays, Bad Teeth, and Matt & Geof Go Flying, have been performed in staged readings in Los Angeles & Portland; he attended writing workshops run by Beyond Baroque, John Rechy, Sheila Finch, John Hill, & A.J. Budrys. He has translated Laura Esquivel into English & several of Croatian poet Tomica Bajsic’s poems into Spanish. Back in the day he co-hosted a floating æther-den (it was the 70’s). He is the founder & editor of Gobshite Quarterly—a Portland, Oregon-based multilingual en-face magazine of prose, poems, essays, reasoned rants, & etc.; & author of a 90-language dictionary of insult & invective, obscenity & blasphemy, Curse + Berate in 69+ Languages (published by Soft Skull); & edited & published a bilingual edition of Luisa Valenzuela’s Deathcats/El gato eficaz.

* * * * * * * * * * * * *

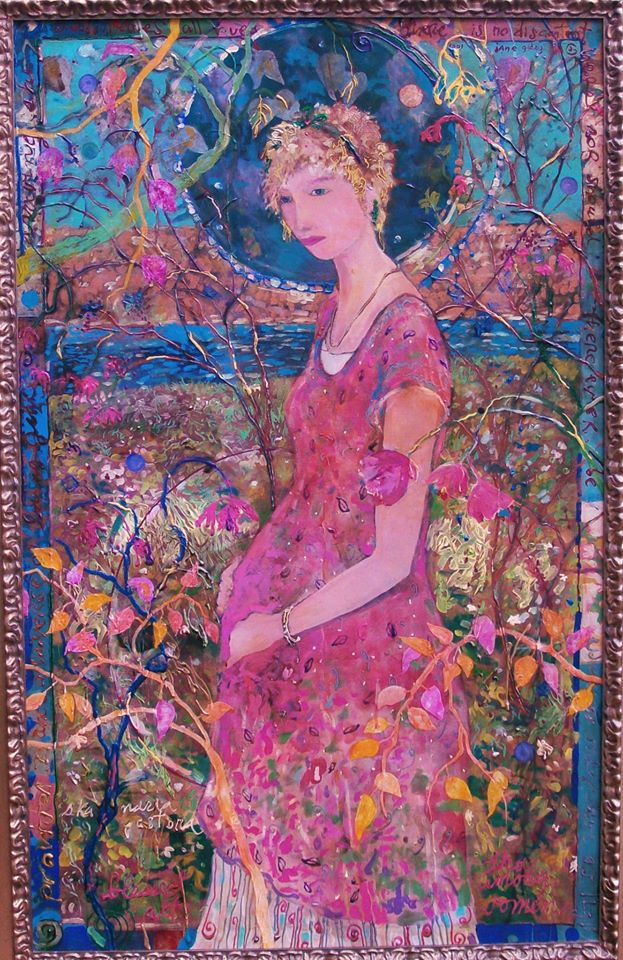

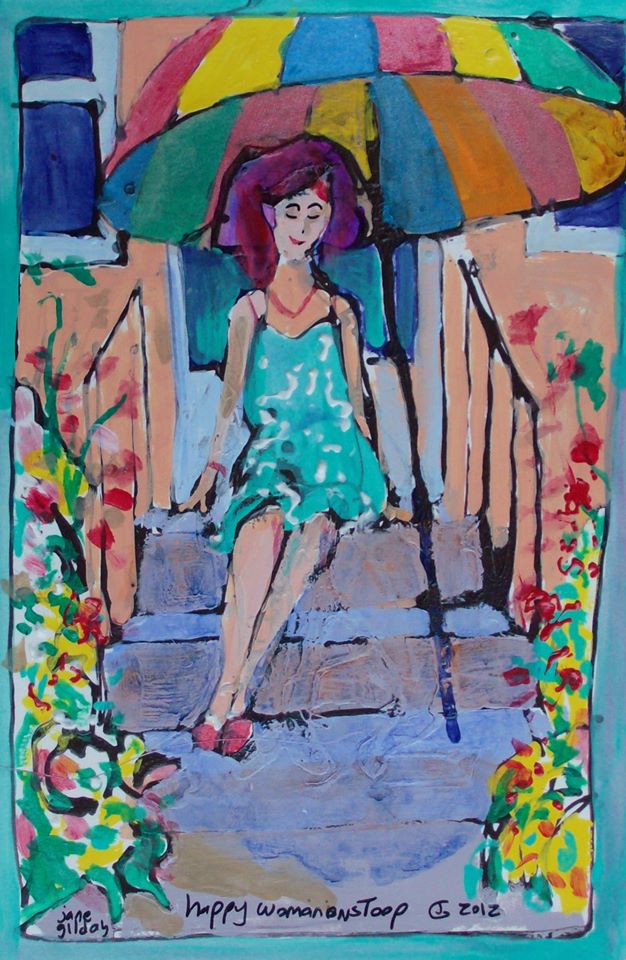

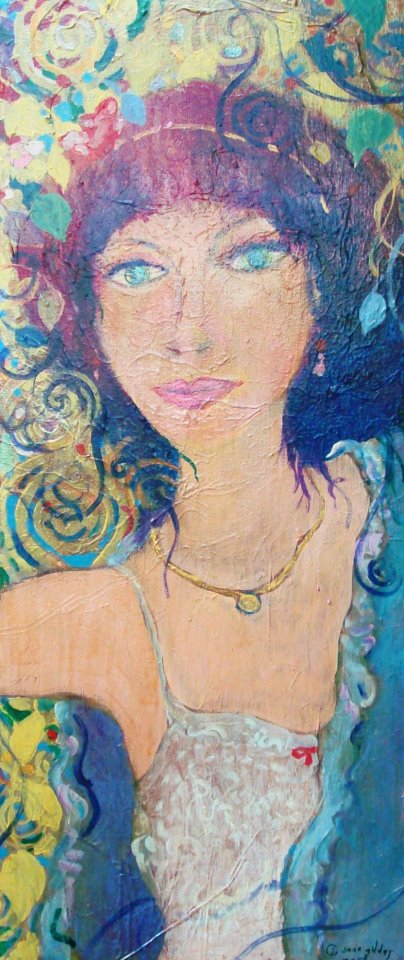

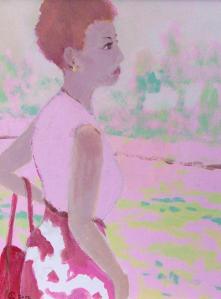

Artist: Jane Gilday

Woman in Pink

Acrylic on archival paper, mounted on board